By Paolo Chua from townandcountry.ph

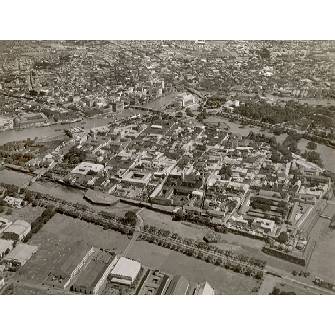

The walled city of Intramuros, Latin for “within the walls,” was the precursor of modern-day Manila. During its heyday, the city was the center of life: business, politics, religion, education, and everything in between.

Intramuros’ residents were mostly made up of Spanish officials and other government servants. There, they lived luxuriously in large bahay na bato which were typically decorated with a mix of European and Oriental influences including lace curtains, Venetian mirrors, opulent chandeliers, and Chinese porcelain.

In Spanish Manila, societal rank was determined through “land dominion and favor with the church.” The rich, upper class lived a relazed and slow-paced lifestyle. A typical day would start at 6 a.m. with a cup of tsokolate and broas. After their morning rituals, they would head to work and stay there until 12 noon. Work would be followed by a hearty lunch back at their homes, and a long siesta (some would nap until 5 p.m.). Before supper, some would opt for an evening stroll, others met with acquaintances to gossip, or browsed through the stores of the Chinese vendors.

On the other side of the coin were the natives who had earned just enough to survive the day. Though they worked inside Intramuros, these laborers lived in nipa huts outside the walled city.

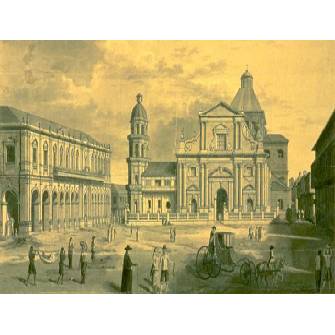

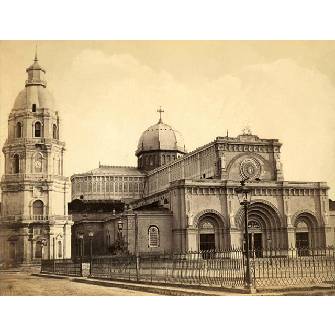

The lives of those who lived in Intramuros were heavily centered on religion. There were several churches within the walls: Manila Cathedral, San Agustin, Lourdes, San Ignacio, San Francisco, Santo Domingo, and Recoletos. The city housed the largest educational institutions: Universidad de San Ignacio built in 1590, Universidad de Santos Tomas in 1611, Colegio de San Juan de Letran in 1620, and the Ateneo Municipal de Manila in 1859.

A Scottish trader named Robert MacMicking chronicled his experiences during visits to the city in “Recollections of Manilla and the Philippines, During 1848, 1849, and 1850.” He writes:

It is usual for a military band to perform before the palace on Sunday and feast-day evenings, and on these occasions many carriages go there from the drive, about eight o’clock, to enjoy the music, and give people a good opportunity for either gossip or love-making, as their tastes or the moonlight may incline them.

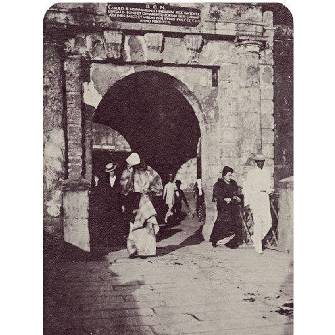

Religious processions are as frequently passing through the streets, as they are in all the Roman Catholic countries of Europe, but the features of all are very nearly identical, and so need not be particularly described.

When one of these processions takes place during the day, an awning is spread along the streets it will pass through, to protect the bareheaded promenaders from the sun, the canvass being attached to the house roofs along the streets; making them incredibly hot to pass along, so long as it remains there.

At night, however, parties or

fiestas were a time for Manileños to let loose. MacMicking shares that back then it was customary for residents to welcome any “respectably dressed Europeans” who happened to pass by a house that was hosting a party. Although he’d virtually be a stranger to those at the

fiesta, the European would then become the most distinguished guest. The man could then ask any lady to dance, an offer that was irrefusable since declining was considered déclassé.

“Medieval Manila: Life at the Dawn of the 20th Century,” a research paper by Jason A. de las Alas states that life in Intramuros was not comfortable by any means. Unlike other metropolises, Intramuros didn’t have any modern conveniences despite Spain's 333-year-long colonial rule in the Philippines. Proper sanitation was practically unheard of and inhabitants had no protection from viral outbreaks.

The alternating heat and rain made the city a breeding ground for mosquitos and in addition to that, waste was carelessly thrown out of windows and onto the streets. Furthermore, Intramuros lacked water, food, and fuel as well as proper sewage and fire prevention.

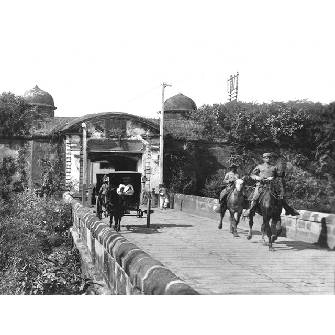

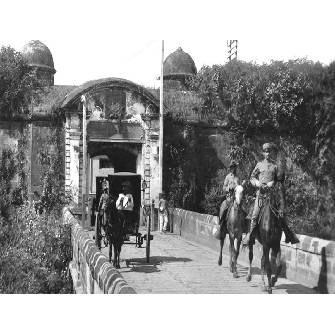

De las Alas adds that traffic was already a problem from the beginning. One of the first bridges to connect Binondo to Intramuros, the Puente de España, was estimated to have accommodated over 6,000 vehicles on a daily basis.

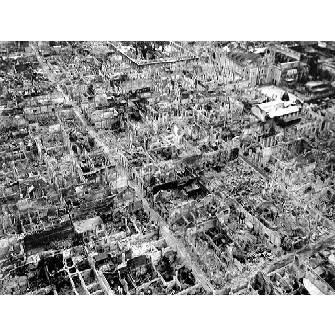

Busy as it was, Intramuros continued to thrive well into the 19th century. The looming First and Second World Wars, however, would forever change the landscape of Manila.

Sources: “Recollections of Manilla and the Philippines, During 1848, 1849, and 1850” by Robert MacMicking and “Medieval Manila: Life at the Dawn of the 20th Century” by Jason A. de las Alas