Every Filipino visits Intramuros at least three times in his life—the first time during his grade school field trip, the second time with his college girlfriend, and the third time when he takes his foreign friends around Manila to give them a history lesson (complete with tour). This doesn’t count unforeseen excursions like future weddings, someone’s third cousin’s golden wedding anniversary, and sudden biennales.

With its baluartes, churches, plazas and palacios, Intramuros is one of our last links to our past. It’s also home to San Agustin church, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It seems like a wide, open air museum peppered with the occasional cathedral and ruin—not quite look-but-don’t-touch, but inspiring just that kind of reverence. It also carries so much historical weight that there’s almost no room in it for the present. But things are about to change.

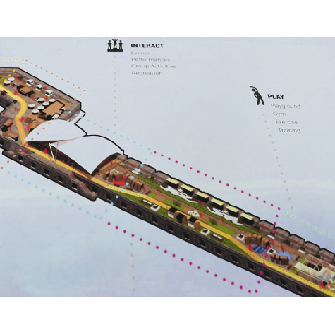

The Intramuros Administration (IA) and the Creative Economy Council of the Philippines (CECP) are working on building a creative hub along the Maestranza Wall—a three hundred-meter structure built along the Pasig River during the 16th century. Composed of forty four chambers (or forty five, depending on who’s counting), the Maestranza was used to store goods during the Manila-Acapulco trade. After it was leveled by the Americans during the second World War, the old structure had to be reconstructed—these efforts began under Senator Dick Gordon during the last years of the first decade of the millennium, and are still continuing now.

Today, the wall chambers are envisioned to be incubation spaces for various creative arts including architecture, advertising, media, and even fashion design. Given that the creative economy is a major contributor to the GDP, the current administration aims to integrate tourism and the creative economy into this one space. “This will be the country’s first iconic Philippine hub,” says Attorney Guiller Asido, head of the Intramuros Administration. “We’re working with the private sector and trying to see for them what we can still use for the space as a canvas for the arts. We will be dividing (the chambers) basically, and using them as incubation spaces where creative services will be properly in place.”

Asido says each cut measures 40 square meters, with the total area housing various creative and commercial spaces. “There will be masters [setting up spaces], for example, or teachers, who will train and impart their ideas, or the proper development of ideas [that will t ake root here].

The adaptive reuse of the Maestranza Wall coincides with the administration’s long-term plans of creating a more dynamic and inclusive Intramuros—one that isn’t just appreciated as an urban heritage district, but one also engaged in a vibrant dialogue with modern times.

“There’s always this presumption that Intramuros is different at night compared to the morning,” Asido says, given that most of the district’s negotiations with the city occur during the day and quiet down at night. After-hours, the district is not a nocturnal animal, it’s a city at rest. It is hoped that its ancient rhythms can adapt to present times. “This will ensure that we’ll be able to—in a way—begin the urban regeneration of Intramuros,” Asido continues, “because artists are coming here already, using the spaces. And hopefully, there will be a better appreciation of the other heritage spaces as well.”

As the administration moves toward the final stages of reconstruction, more concrete plans for the wall are already underway. “What we’re doing right now is planning the interiors,” Asido says, “what we intend to do already is to maximize the use of the spaces.” He adds that the creative hub will be completed in 2020, hopefully ushering in a new age for Filipino heritage and creativity.

If these chambers heralded the beginning of globalization in the sixteenth century, their adaptive reuse in the near future can also be seen as a new globalization of ideas and creativity. Perhaps future excursions to the walled city can include this new warehouse of ideas where the Filipino mind can take flight among the old bulwarks and places of worship. It’s especially poignant to think that we could be moving toward Rizal’s dream nation literally a stone’s throw away from where he took his last steps. It’s also novel to think that Intramuros could finally be a living district, and not just the walled city we reserve for field trips, weddings, and occasional kalesa rides. And the second biennale, which, when we think of it, should also take place in 2020.